The Shift from IPOs to Private Capital

Recently published academic studies by Ewens & Farre-Mensa (2020, 2022) point to some of the reasons by which start-ups can remain private for longer time. Part of such reflections were also contrasted in a recent Financial Times article. They notice a new wave of massive start-ups that is redefining the path to growth by delaying IPOs. Instead of going public, companies like Databricks, SpaceX, and OpenAI are leveraging billions in private capital to scale while avoiding public market scrutiny.

For instance, Databricks raised a record-breaking $10 billion in late 2024. Similarly, SpaceX and OpenAI raised $1.25 billion and $6.6 billion, respectively. These companies are using private markets to operate at the scale of public companies—without needing an IPO. But why? Well, actually they already have access to huge private funding pools. Companies like Databricks and Stripe are raising so much private funding that it’s almost as if they’ve “gone public”—just without the IPO. Secondly, the absence of an IPO gives them flexibility and reduced scrutiny. Staying private allows these companies to avoid quarterly earnings pressures, activist investors, and public market oversight. This freedom also lets them focus on long-term goals and innovation rather than short-term performance metrics. Though private markets offer flexibility, they lack the transparency of public markets. Without public scrutiny valuations can become inflated, which public markets help keep in check.

One reason start-ups are staying private longer is the 1996 National Securities Markets Improvement Act (NSMIA). This legislation made it much easier for companies to raise private funding without the complexity of state regulations. Previously, companies had to follow both federal and state laws when raising money. NSMIA allowed companies to raise money under federal rules alone, enabling start-ups to tap into larger pools of out-of-state investors. For example, a VC firm in California could now easily invest in a Texas-based start-up. This spurred the growth of private markets, enabling late-stage start-ups to raise larger funding rounds and scale like public companies.

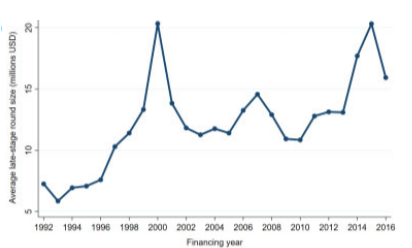

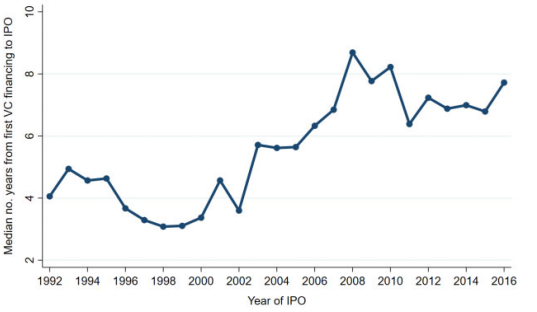

Ewens and Farre-Mensa (2020) noticed an explosion in the private market, where late-stage funding rounds significantly grew after 1997, with averages sizes jumping from around $7M (1992–1995) to over $10M after 1997. This also resulted in longer timelines and resulted in fewer IPOs, in such a way that the median time to IPO increased from 4 years (1990s) to 8 years (2016). Start-ups achieved significant growth and valuations without ever going public. Ewens and Farre-Mensa also mentioned non-traditional investors who drive growth: hedge funds, mutual funds, and private equity firms now contribute over 70% of late-stage funding. Which fueled the rise of U.S. unicorns from 0 (in 2002) to 130 (2019). Managing a non-IPO company also meant that founders were able to retain more equity. Founders sold 46% of their equity in Series A-rounds in 2002 and dropped to 30% by 2019. This allowed them greater control over their companies.

These studies showcase why start-ups like Databricks, SpaceX, and OpenAI, are thriving without going public. They use the strength of private markets to grow, reward employees, and attract significant funding, all while avoiding the short-term scrutiny and regulatory pressures of public markets. However, this shift raises concerns about transparency. Private companies, while benefiting from flexibility, don’t face the same rigorous checks as public companies, highlighting the need for balanced policies that foster innovation while ensuring accountability.

Related content

You may be interested in this articles too